Stylish Cottage for Katrina Country Is a Big Hit Click here to refresh: http://www.newherbanism.blogspot.com/

A well-designed home for under $50,000? This tiny house designed for the battered Gulf Coast will be sold by Lowe's, and is expected to draw buyers from all over.

A model home in Ocean Springs, Miss., that gives Katrina's displaced an alternative to trailer living is starting to take the country by storm.

The Katrina cottage -- with living quarters about the size of a McMansion bathroom -- is now appealing to people well beyond the flood plain. Californians want to build one in their backyards to use for rental income to help with the mortgage payment. Modestly paid kayakers in Colorado see it as a way to finally afford a house. Elsewhere, people envision building one so a parent can live nearby.

A new niche flying in the face of a "big house" trend, designers of these tiny abodes seem to have found a new housing niche. Some experts cite an interest by some Americans in downsizing their habitats, a reaction to the supersized home, and note the challenge of heating and cooling a big house at a time when family budgets are flat. Others note that changing demographics -- more empty nesters and single adults -- may mean a timely debut of the Lilliputian homes.

"It's resonating with people because it's a market that did not exist," says Marianne Cusato, a New York-based designer who drew up the plans for the Katrina cottage. "In the past, you had to go either to an apartment or a trailer."

Commercialization of the concept is limited -- but that is about to change. Late this year, perhaps as soon as this month, Lowe's, a national hardware and building-supply company, intends to begin selling the plans and materials for four models in 30 stores in the Gulf Coast region.

The "Lowe's Katrina Cottage" offerings range from a two-bedroom, 544-square-foot model to a three-bedroom, 936-square-foot house. The cottages will cost $45 to $55 per square foot to build, Lowe's estimates, meaning the smallest would run about $27,200 and the largest $46,800. Estimates do not include the cost of the foundation, heating and cooling, and labor.

"We're starting on the Gulf Coast, where the original idea came from, but as soon as we feel the logistics are worked out we could go national," says Cusato, whose

Web site has received more than 7,000 inquiries since January. "We want to be sure that when we say it's available, we're 100% sure we can deliver."

A concept that could spreadIf Lowe's is successful, it's likely other companies will offer their own designs. "There is such a huge opportunity, when you talk about the number of houses that need to be built in Mississippi and Louisiana, that I think a lot of folks are looking at this type of concept," says Dan Tresch, director of governmental affairs at James Hardy Building Products, which provides the siding for Cusato's cottages.

One of those other companies won't be Home Depot, the Atlanta-based supplier of building materials. "We assessed the opportunity but chose to pass on selling them," says spokesman Tony Wilbert.

Although Lowe's has not started marketing the houses yet, the original Katrina cottage has been featured on television and in newspaper articles. As a result, Cusato gets queries every day from around the world. Some of the e-mails and letters envision the cottages as college dormitories, military housing, homeless shelters, zookeeper's offices and rental properties.

Among the recent inquiries was one from Keith Rogerson, a city councilor from Bridgeport, Conn. "We have lots that are too small for a … single-family, detached household, so the idea is to bring in these extremely attractive dwellings to provide affordable housing," says Rogerson. "We're also looking at reorienting the zoning so we can put them in clusters to stave off ghettoizing the city."

The Katrina cottage concept inspired Norman Bradshaw, a retired deputy sheriff in Tallahassee, Fla., to call Lowe's. He's thinking about moving to a farm in Georgia. "What I'm trying to find is something affordable in the $65,000-to-$75,000 range," says Bradshaw. "Right now, the only thing you can afford is a trailer, and they are so flimsy you can put your fist right through a wall." If Lowe's follows though with the original design, Bradshaw says, he'll buy one.

Urban planners and architecture critics are generally enthusiastic. "Designers have done a good job with toasters and cars, and now they have done housing -- and it couldn't have come at a better time," says Anthony Flint at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, a think tank in Cambridge, Mass. Architect Sarah Susanka, author of "

The Not So Big House," calls it "a charming, tiny house with character."

The cottage, though almost doll-size, manages not to feel claustrophobic in large part because Cusato has included a wide porch. "If you live in a small house, you need a proper outdoor room," Cusato says. "In addition to making the house larger, it engages you with your neighbors."

Ready for hurricanes and add-ons Cusato's design also calls for steel frames and James Hardy's fiber-cement-board siding. It's rated to withstand a hurricane with 140-mile-per-hour winds. The siding makes it termite-resistant, noncombustible and immune to rot. One intangible aspect of the house: It is designed to be easy to add on to.

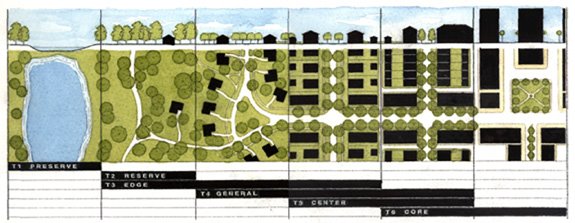

The idea for the cottage came during a planning session in Mississippi. Gov. Haley Barbour had asked Andreas Duany, a Miami urban planner with the firm Duany Plater-Zyberk, to participate in the post-Katrina Mississippi Renewal Forum. There, Duany challenged designers to come up with an alternative to the trailers from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Cusato's design was picked as the winning effort.

But the concept didn't really take off until January, when the cottage made its debut -- almost by happenstance -- at the International Builders Show in Orlando, Fla. Susanka was set to build a small, modular show house for the event, but her sponsor pulled out. Duany suggested that Cusato's cottage go in its place -- and it was an instant hit with developers, who clamored for the plans.

The house was then trucked to Ocean Springs, Miss., where thousands of people have explored its confines. Cusato sees the cottage as one way to help the region recover. "If you give people a decent place to live, they will want to settle in," she says. "The most sustainable thing you can do is build something that everyone loves and everyone wants to keep."

Source: Ron Scherer, The Christian Science Monitor, October 2, 2006